Sometimes the art-making process is a sacred thing. Other times it’s fart trumpets and poop jokes. Nobody knew this better than pre-modern artists: Members of a movement that found its roots in the classical and medieval period, Renaissance artists are best known for the stunning paintings of 14th to 16th century Italy, like “The Birth of Venus.” Then there’s Hieronymous Bosch, the 15th century Dutch painter whose most famous work is a triptych of Eden, Earth, and Hell called “The Garden of Earthly Delights.” His overwhelmingly detailed panoramas tell a hundred stories in one. While their overall subject matter is serious, those little stories create a collage of Earthly life that’s both comedic and surreal.

Richardson’s games are dioramas that talk back, chunks of the past that threaten sensory overload

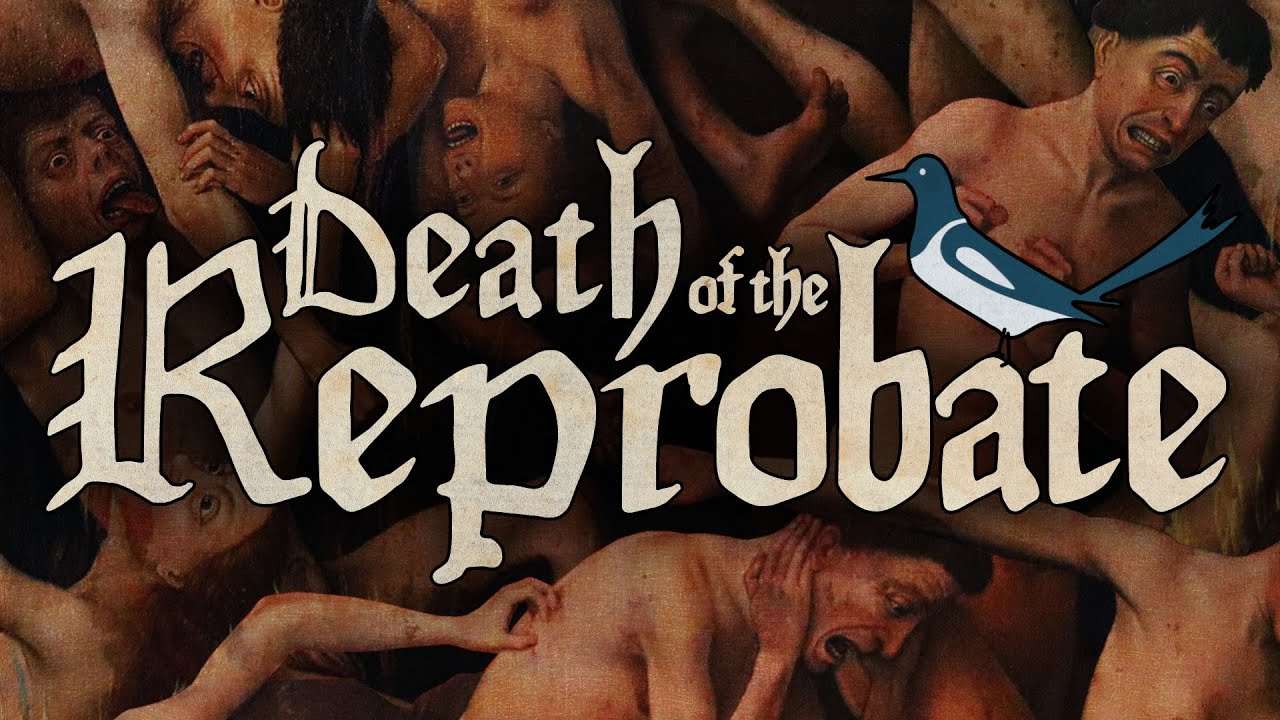

It makes sense then that Bosch’s painting “Death of the Reprobate” is the inspiration for Joe Richardson’s newest game of the same name, out today on Steam. His follow-up to 2020’s The Procession to Calvary is a point-and-click adventure made out of the artscapes of the Renaissance. To play it, you navigate your character through the composite paintings Richardson’s made, doing seven good deeds so your dying father (the reprobate in question) will pass the crown to you.

Bosch was the starting point for the game for another good reason: he was one of the only Renaissance artists Richardson knew.

“When I decided to work in this style [Bosch and Bruegel] were pretty much all I knew of Renaissance art. Even after delving into the depths of the museum archives and casting my net a little wider with each installment, he remains one of my favorites,” Richardson says.

Richardson’s humor gets its bodily fluids and physical comedy from his pre-modern inspirations, which were vividly aware that all the five senses can be funny. As you try to complete those seven good deeds, you can interact with each character in three ways: looking, talking, and touching. You can poke two people having sex in a barn, flirt inappropriately with a runaway bride, and flee from the overwhelming sound of a room crowded with screaming children. The sights, sounds, and smells of the city you’re running around mix with anachronistic-on-purpose modern humor, like when a loom operator jokes about creative numbness or a pagan god responds to religious fervor with “Bro, chill.” It’s a surreal blend.

Richardson’s history with art began with Flash animation collages of cut-up photographs before he studied 3D modeling. In his first game, The Preposterous Awesomeness of Everything, he used photo montage to create human models with exaggerated facial features and bright backgrounds that often clash with the characters and UI. Richardson admits the game was grotesque on purpose—”I was still an art student at the time, forgive me”—but it’s what gave him the idea to make a more visually cohesive world from collage, an idea that would become his first Renaissance puzzle game Four Last Things.

I was curious what drew Richardson to Renaissance art in particular, and it’s the visual composition, rather than previous familiarity with the subject, that he says made it appealing. Scenes in the game can have elements from between one and a hundred different paintings, all found through Richardson’s searches through gallery archives and Wikipedia entries. Musicians play harps and cellos in the foreground while extras on rooftops in the background hit each other on the head with brooms, and interactable characters yell, sleep, get high, and watch birds in between the two.

Spoken lines become ink on parchment, complete with typos and emoticons. The whole thing ends up looking like a manuscript broken down into pieces.

Richardson has collected 4,022 paintings in total across his three projects, and estimates that only a third of them appear in the games—though that’s still probably a record for Renaissance art in any game. Although compositing them into the same scene requires some manipulation, his goal is to alter each original image as little as he can.

“Basically every creative decision I make is led by the artworks: I make all the background art first, before any writing or puzzle design. I’m always moulding the dialogue and the puzzles to fit around the art, not the other way around,” he says.

Although this makes it sound like the puzzles are an afterthought, they fit in with the surrounding collage world. The best example is an early puzzle where you can swap out the background, foreground, and subject of a painting in an art gallery. Then when you return to an earlier screen, you find that real life has imitated the changes you made. It’s funny to give a guy a cabbage head for no reason, but it was also a moment where I realized the cosmetic and play elements of Death of the Reprobate were truly entwined.

You might expect the person who developed these puzzles to have a soft spot for them, but Richardson feels differently. “I hate puzzles!” he says. (I can’t quite tell if he’s being serious.) “For me they’re just there to give you an excuse to be in the world. They give the player a purpose and encourage them to explore, but I don’t find them inherently fun. [And] making a fun interaction from a pre-defined set of objects [like the paintings] is sometimes a bit of a nightmare.”

Writing the script for the game, though, provoked the opposite feeling. “There is so much already in these artworks, my idiotic misinterpretation makes them immediately funny to me,” Richardson says.

Juxtaposing the elements of many different paintings, many of whose themes contradict each other, allowed him to craft jokes without writing a line of dialogue. And there’s moments where just describing what’s on screen—like “Fully Clothed Lute-Bearing Adult,” “Affable Sky Wench,” or “God Almighty” (who is your tutorial guide)—is funny in and of itself.

Richardson’s games are dioramas that talk back, chunks of the past that threaten sensory overload. While I definitely can’t call Death of the Reprobate an educational game, it’s possible to learn about many, many paintings and artists from the in-game gallery, which is built from all the works collected during the development process.

Despite developing a following over the years, Richardson doesn’t take any success he’s received for granted. “Making games has always been a struggle for me, and selling games, even more so. So if my games are remembered at all, I will be happy as fucking Larry,” he says.

Though Richardson is humble about his games’ influence, I hope they’ll inspire players to learn more about the art they contain, and maybe inspire game developers to borrow from art history too.