Deathbound is set in a grim sci-fi future where religious fanatics and science freaks are locked in a mysterious, verbose conflict. In this harrowing dystopia, many doors only open from one side and ankle-high objects can obstruct passages. The art style is an interesting blend of noir, neon-lit sci-fi and fantasy elements that put me in mind of Castlevania: Lords of Shadow 2, and while it’s undeniably a soulslike it breaks the genre’s tradition of stoic quietude: this is a very chatty game, with a labyrinthine narrative that doesn’t shy from a spectral flashback.

A new soulslike must have a twist, and Deathbound has its party system. This doesn’t mean you’ll be roaming the neon-lit ruins of Akratya city with three friends in tow: it means you can swap between a total of four characters on the fly (there are more than four characters, but you must select four to load out with). As I moved through the mostly linear but occasionally shallowly interconnected zones of Akratya I’d occasionally find new party members, like Anna, a trashmouth assassin, or Haodai, an unfailingly sincere “essencemaster” (a mage, basically). There’s uber-serious spearwielder Iulia, a heavy battle axe-wielding misanthrope called Agharos, and—most unusually—a monk, Mamdile, who specialises in the Afro-Brazilian Capoeira style of martial arts. Rounding out this gaggle is the self-flagellating former lord Therone, a sword and board guy, and another character I’m yet to unlock.

Each character has their own playstyle and is satisfyingly distinct. My favourite is Mamdile, whose hand-to-hand combat is leavened by a generous parry window and flexible manoeuvrability. I usually navigated the areas as the versatile Anna, whose rapidfire dagger rips and tears are complimented by ranged bolt throws, though Haodai was a useful sniper, albeit at the mercy of a Heat meter which ensures that spamming magic projectiles and buffs will result in a literal overheating (he explodes, basically. Thankfully not fatally).

I didn’t really main a character, though. You’re not meant to: Deathbound is all about circumstantial swapping and it hugely incentivises—nay, requires—on the fly switches mid-combat. There’s a five-bar sync meter that is filled by regular attacks and perfect dodges, and switching to another party member after a successful hit can spend one of these bars, triggering an immediate “morph strike” from the newcomer. When the sync meter is completely full, pulling off a successful ultra morph strike can dole out a devastating blow that will usually carve most of the health off heavy grunts. It’s the difference between a slow and boring war of attrition and near-instant victory.

Instead of chugging estus, the active party member heals the other three by dealing damage.

It’s a cool idea that evolves Nioh’s stance switching system, but it’s difficult to execute reliably. I understand that soulslike orthodoxy rules out the canceling of hastily triggered moves, but pulling off a sync at close range is a risk not often worth taking. If I fire off a few projectiles as the mage, and then sync into the spear-wielder to issue a brisk bleed-happy jab before pulling off a perfect dodge, and then sync into battle axe dude for a big hit from behind, each move needs to play out in its entirety—without getting hit!—or else I’m going to cop a flogging, and that’s factoring in the brief moment it takes to actually perform a sync. It feels like a long time when you’re facing unpredictable enemies with fast attacks. It’s especially galling when my sync meter is full and I pull off a super melee attack, only for that attack to not land. Timing can feel tedious rather than satisfyingly precision-focused.

Stamina management is also of urgent importance because all characters have their stamina docked according to their health pool. That means if you’re on a slither of health, you’re on a slither of stamina too. This is yet another incentive to always be switching, especially since there’s no effective item healing save one that boosts the users health and docks everyone else’s. Instead of chugging estus, the active party member heals the other three by dealing damage.

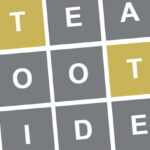

There’s another layer of complexity to do with the party members themselves: some of them hate one another (and boy, are they loud about it!), while others have affinities. Party selection is done via a diagram showing the interplay of your selected load out. If characters are connected via a blue line, they enjoy certain advantages, but red lines mean some debuff or disadvantage will be in effect:

More egregious is the level design, or more specifically, the furniture placement. For a game that likes to throw barely visible snipers at me on the reg, there sure are a lot of annoying ambiguities regarding what I can walk on and what must be walked around. I was feeling pretty disenchanted already when, entering a giant rundown stadium, I was made to navigate the seat aisles towards sniping enemies. Ankle-high boxes—in one case a little speaker!—laid in the aisles are enough to prevent my hero from entering that aisle. These lapses in logic are easily forgiven in games if they don’t hinder us, but boy do they hinder us in Deathbound. If I’m not confusedly navigating a stupid maze like this while dodging near-invisible poison bolts, I’m getting stuck on objects while an enemy pounds away at my face. Or, a long-armed freak is hitting me through walls while I can’t even swing at an enemy near furniture without the furniture obstructing my blade.

All this results in a game that annoyed me despite my efforts to really like it. There are droves of soulslikes and all have their bullet-point twists. In Lords of the Fallen you’re switching between playable shells. In Lies of P you’re Pinnochio, with stance shifting. In Another Crab’s Treasure you’re a crab. I think Deathbound’s “twist” is my favorite for the way it shaves away number-crunching complexity in favor of on-the-fly party management. I’m not sure if its shortcomings can be fixed post-launch or not, but for now it’s a perfect case of an amazing concept undermined by poor execution.