“It’s an obvious kind of a thought,” says Irrational Games co-founder Jon Chey. “What if XCOM wasn’t a turn-based game? What if you were one of the operatives, as opposed to just clicking on a map with them?”

It’s a question that wound up defeating Irrational. Renowned as one of the most creative outfits in the history of gaming, the developer conceived BioShock and its cloud-surfing sequel, Infinite, alongside deeper cuts like SWAT 4, Freedom Force and System Shock 2. But it never quite got a handle on its XCOM shooter. The winding path and dead ends of XCOM’s development eventually contributed to the departure of senior figures from Irrational’s Australian studio. But as you’ll hear, that creative spark was never diminished. And today, all those bold experiments and prototypes have led to a spiritual successor that finally accomplishes what Chey and his colleagues were reaching for.

Alien origins

The genesis of Irrational’s XCOM project was the company’s acquisition by 2K. “We’d already started working on BioShock, so that was a property that we brought to the table, and they agreed to continue,” Chey says. “They injected a lot more resources into it, and enabled us to be much more successful with that than we would have been otherwise.”

Irrational Games was two studios—one run by Ken Levine in Boston, USA, and another led by Chey in Canberra, Australia. Since BioShock was Levine’s baby, it seemed natural that the Boston office would lead that project. Which left a question: what would the Australian studio do? “We did end up doing a lot of work on BioShock,” Chey says. “But originally the idea was that we would have two projects, and each studio would manage their own project.”

At that time, Firaxis was half a decade away from producing its own XCOM: Enemy Unknown—a faithful, streamlined take on the alien invasion premise that saw turn-based tactics enter the mainstream. But Chey and Levine were both huge fans of the 1994 original, and acutely aware that 2K owned the rights to the series. They speculated about what it might be like to make an FPS spin on XCOM.

“Finally we’d realised, with the advent of first-person, that turn-based was a bit of a niche,” says Ed Orman, who worked in Canberra as lead designer on the XCOM project. Irrational had made two Freedom Force games—tactical superhero battlers which encouraged the player to pause the game and think through their next moves. Though critically beloved, they never sold particularly well. “You’re not going to hit the big numbers,” Orman says. “And we were working on BioShock, which is a first-person shooter. So if we’re doing that, why don’t we have a crack at a first-person version of XCOM?”

2K responded well to the pitch and gave Irrational the go-ahead to start testing out its ideas. “Prototyping is a great process, and I’m glad that 2K gave us the room to do it,” Chey says. “They were actually very accommodating with that.”

Why don’t we have a crack at a first-person version of XCOM?

Jon Chey, Irrational Games co-founder

Irrational quickly identified the core challenge of the project: turning a game about managing a team of soldiers into a solo FPS. “First-person shooters have really struggled with the notion of managing a group of people,” Chey says. “You have your AI companions who run around in front of you and get shot, or they run off and do something else, or they kite the enemy into attacking you when you don’t want them to. It’s very, very hard to make them behave sensibly and give you a feeling that you’re managing them and not get overwhelmed.”

Irrational had previously grappled with friendly AI during the making of SWAT 4, which solved the problem by tying your squad commands to corridors and entryways. “It is very tightly wedded to this notion of clearing rooms,” Chey says. “Stacking up and then entering and this brief moment of combat. We could have done an XCOM game that was very room-based. But that would have caused some problems too, because the original obviously takes place in a much more varied range of environments outside. You can take cover behind trees and hedges.”

The team looked at Brothers in Arms—which wasn’t short on hedgerows, had a tactical command system, and modelled something XCOM had always leaned into: fear. “Brothers in Arms had done a really good job of the expression of morale in a real-time, first-person setting,” Orman says. “I know we were looking at that as a reference point. The twisted road it then went through over the next seven years, it went through so many different iterations.”

The chief inspiration in the beginning was Full Spectrum Warrior—a hardcore military simulation that came to PC and consoles in 2004. “It was real-time but had a turn-based feel to it,” Chey says. “Because everybody gets into cover, and then it’s basically a static situation. And then you can choose an order which moves the situation forward. You send some people to flank, or you do something that causes the enemy to pop up, and then you can respond to that.”

Irrational’s first XCOM prototype followed that formula. It was a “pretty cool” shooter designed to give the player time to think about their tactical situation. But internal feedback suggested it was too niche. “I think Full Spectrum Warrior was a bit niche too,” Chey says. “It’s not the way that your average FPS player wants to think—it’s very deliberative and tactical. The feeling was that it was missing the mark a bit. Even though that’s what XCOM is—it is a very tactical game.”

Tellingly, in solving the problem of a real-time XCOM to its own satisfaction, Irrational had built something it couldn’t sell. “That already exposed the tension,” Chey says. “It sounds great when you say, let’s do a first-person shooter XCOM. But they’re different worlds. So how do you bring them together?”

One alternative idea was to lean into the spectacle and cinema of Call of Duty. Irrational imagined an XCOM game about kaiju-style monsters attacking cities. “The whole game would be about the scale disparity, that you were little human soldiers,” Chey says. “The aliens have brought these huge creatures as part of their invasion force, and your job is to take them out. And you have to do that by actually, Shadow of the Colossus style, getting onto them and running around, planting a bomb at the base of their spine to blow their head off.”

Monster mash

Chey references the sequence in Starship Troopers in which protagonist Johnny Rico rides on the back of an enormous beetle-like Tanker Bug, blowing a hole in its carapace in order to bury a grenade beneath its shell. “The scale would be enormous, even bigger than that,” Chey says. “Maybe like the sandworms in Dune, the size of entire city blocks. You’re running around, maybe you even go inside them and fight through them and then come out somewhere. We prototyped that.”

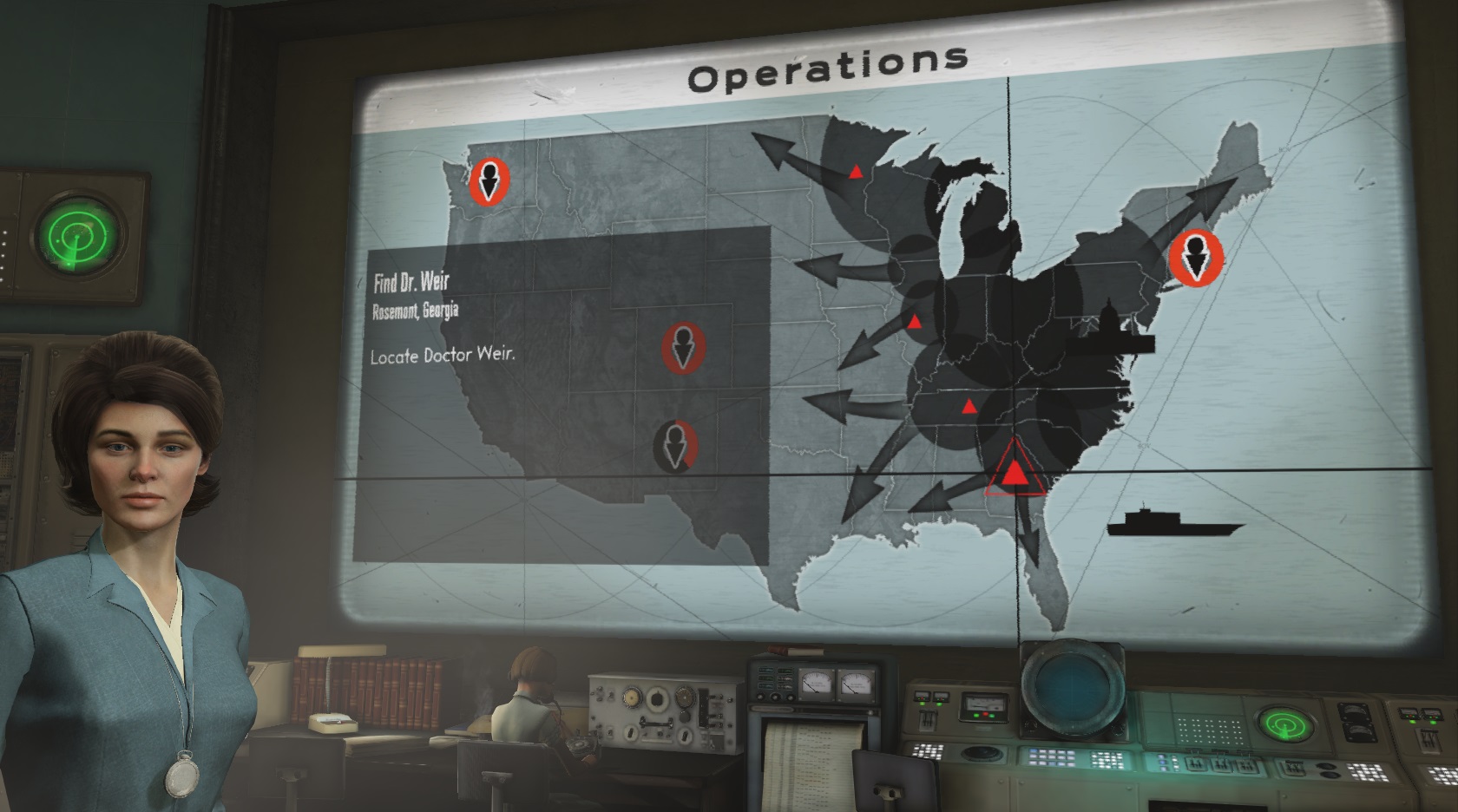

XCOM operatives would combat Godzilla-level threats by piloting a flying base—from which you would receive word of alien attacks across the globe and pick your next mission to counter them. “It was transferable all around the world, and we were dropping in from low Earth orbit,” Orman says. “It was all seamless in real-time. We built the fricking thing.”

Chey doesn’t remember why Irrational stopped working on that particular prototype. “It might have been just because we felt like it was getting too far away from what XCOM was supposed to be about,” he says. “It is a fun idea. I just don’t know if it was the right idea for XCOM. The original is not a game about giant monsters.”

At one point, the Boston office had a bash at a concept in which you joined a resistance organisation in the aftermath of the events of the original game. “Which I guess is a bit more like Firaxis’ XCOM 2,” Chey says. “The aliens have taken over the world. The idea was that your job was not just to attack or infiltrate the enemy’s bases, but to instigate a popular uprising.” This version of XCOM was still a shooter, but you would conduct operations with the goal of inspiring local insurrection. “We developed some good inspirational mock-ups of what that game would feel like,” Chey says. “But I don’t know that we ever really solved how the mechanics would work and how it would come together as a real game.”

Because we were using aliens as the character classes, it just gave us an excuse to do whatever the hell we wanted.

Ed Orman, lead designer

Then there was the asymmetrical multiplayer mode that Irrational worked on, which made playable characters out of the aliens you would encounter in a solo campaign. “Since we had this very asymmetric game of humans with conventional weaponry and really bizarre aliens, that would probably be fun to do as a multiplayer game,” Chey says. “Where you’ve got completely different capabilities. It’s an idea that other people have had and I don’t know if it has ever really taken off in a big way. It’s very hard to do because you’re kind of making two games at once. Balance is hugely difficult.”

Nonetheless, the mode was a lot of fun. Over the course of a single match, it mimicked the shape of a whole XCOM campaign—with the humans starting out on the backfoot, but gradually building up their abilities to equalise. Orman remembers a lot of “weird, cool mechanics that I’ve still not seen replicated in other games”—and which he still won’t tell me about, in case he finds a way to repurpose them in a future project. “Because we were using aliens as the character classes, it just gave us an excuse to do whatever the hell we wanted,” he says. “And so there were a lot of cool mobility things that the aliens had that the humans didn’t. A lot of powers. I’m trying to be vague.”

Eventually, Irrational landed on a singleplayer premise it felt worked—a prequel to XCOM set in 1950s America. “The ’50s was all about Project Blue Book and the aliens,” Orman says. “So let’s lean into that vibe and have them attacking suburbia. That’s the one I really loved. I liked everything leading up to that, but I really loved the setting.”

This was the XCOM FPS that was shown to press at E3 2010. It took place in an idealised mid-century suburbia, a little like that of pre-war Fallout. In the reveal trailer, a housewife was disturbed chopping vegetables by federal XCOM agents in suits with suspenders, only for her face to dissolve before their eyes. The game posited that a terrifying alien force lay dormant in ordinary American homes, in the style of Invasion of the Body Snatchers—a force that quickly became overwhelming when confronted.

“It was a more horror-based approach for the game,” Chey says. “The idea was, let’s make a game that is really tense and has bizarre alien enemies who behave in ways that are completely outside of your understanding, expectation and experience.”

In Europe, the original XCOM had been called UFO: Enemy Unknown. Irrational Australia lifted that subtitle for its own project—hoping to recreate the sense of bewilderment that characterised the turn-based tactics classic when introducing a new type of alien.

“It would be a game that would really focus on the notion of, you’re a bunch of guys with conventional military equipment, and you’re fighting enemies that are operating on this other dimension,” Chey says. “It would be about jump scares and discordant music, and not being sure what you’re looking at. Which I guess is a departure from XCOM, which is much more pulpy.”

Irrational came up with enemy concepts that would be tough for players to wrap their heads around. One, which starred in the trailer, was an amorphous black blob, which as Chey notes resembles the mimics later seen in Arkane’s Prey. “This formless black goo was a kind of stealth monster that could squeeze into little spaces and crawl through openings,” Chey says. “It would drop on your soldiers’ heads, and you couldn’t shoot it because you didn’t want to shoot them.”

Snapshot

In desperate first encounters, the player would use a camera to photograph the aliens, then bring that evidence back to base to research their opponents—ultimately coming up with more effective ways to fight them. In an echo of the Godzilla-style prototype, Irrational planned to confront the player with monsters on a huge scale. “They would stomp around outside and you’d have to take cover inside the house and shoot at them,” Chey says, “while trying not to attract their attention.”

In the trailer, an electrified obelisk named the Titan bears down on the player in the street. The last surviving agent is ultimately killed by a massive, ominous ring which, at a squint, looks like the original XCOM’s Cyberdisc. These radical reinterpretations of 1994’s monsters—designed to counter the silliness of those pulpy designs—are not the kind of thing you could confidently aim a rifle at.

“Looking back on it, and I take responsibility for this, I think we should have committed more to reproducing as far as we could what XCOM was about,” Chey says. “People who loved XCOM wanted to see the same creatures from the tactical game in first-person, and duke it out with a Muton and a Sectoid. They may not be the most original monster designs ever, but they’re part of what people love.”

Frustrated with the churn of XCOM and struggling to find his place in a large organisation like 2K, Chey left Irrational in 2009. “We spent years trying to get somewhere with that project,” he says. “I wouldn’t describe it as the high point in my career. I didn’t really feel like I had made the sort of progress that I wanted to, and like I was contributing a lot and being the person who could make that project successful.”

We spent years trying to get somewhere with that project.

Jon Chey, Irrational co-founder

Orman, who ultimately became XCOM’s design director, left Irrational months after the E3 reveal. By that time, Irrational Australia had been officially folded into 2K Marin—the BioShock 2 studio that was supposed to be assisting XCOM’s development in a support role, but in fact made up the majority of its staff. An 18-hour time difference didn’t help the two studios communicate. “There was a lot of tension,” Orman says. “We’d basically been separated from the Irrational Boston guys, we were no longer allowed to talk to them. So things really fell apart there. We could not work together with the 2K Marin people. It just didn’t work out, so we couldn’t get enough progress on the game.”

After Orman’s departure with art director Andrew James and senior programmer Ryan Lancaster to found Uppercut Games, the direction of XCOM shifted to 2K Marin. That team rebooted the project as a tactical third-person shooter named The Bureau: XCOM Declassified, which launched to mixed reviews in 2013.

In many ways, Chey has been grappling with the XCOM problem ever since. The first release of his indie studio, Blue Manchu, was a turn-based tactics game which took place on a grid, much like the 1994 classic. “I wonder if Card Hunter was a reaction to being unhappy with not being able to make XCOM work,” he says now.

Since then, his team has produced two games in which the player flits between a turn-based strategic layer and FPS battles: Void Bastards and Wild Bastards. The latter in particular, which we scored 91%, bears a striking structural resemblance to the original XCOM. It tasks you with managing the equipment of up to 13 outlaws, choosing which soldiers to pair up for combat, and dealing with injuries that can take them out of battle. As with Irrational’s take on Enemy Unknown, information on your enemies is a valuable commodity in Wild Bastards—allowing you to properly prepare before engaging in an FPS skirmish and risking your outlaws.

Wild Bastards might be something of a niche shooter when compared to the audience 2K was looking at for XCOM. But it’s given Chey some closure. “It’s definitely been a thing that’s been living in my head since leaving 2K: I’d really like to come back to this and figure out how to make it work,” he says. “Because I wasn’t able to make it work when I was there. Wild Bastards is pretty different. But for me, it’s enough proof that you can mix that sort of strategic game with an FPS.”