In this live service era, it’s not that strange to spend years playing a single game, but alongside my various online timesinks there has been one anomaly: a staunchly singleplayer, offline horror game. Alien: Isolation just turned 10, and for this entire time I’ve been trying very hard to muster up the courage to finish it. After a decade of sweating and yelling I finally did it, only a couple of weeks ahead of Sunday’s anniversary.

Back in 2014 I joked that it was going to take me forever to get to Alien: Isolation’s credits, but I didn’t actually think I’d be chipping away for this long. I also didn’t expect it to so perfectly capture the atmosphere of the first and greatest Alien movie, nor the behaviour and terror-inducing effectiveness of the titular xenomorph.

It was this potent mix of skin-crawling tension and heady dose of nostalgia that delayed the conclusion of my journey through Sevastopol Station, precariously orbiting the gas giant KG-348. Every time I fired it up, hoping to make some meaningful progress, I’d be flung all the way back to my childhood—lying in front of the TV, and then hiding under a blanket, praying Ripley and Jonesy would make it.

While the multitude of silver screen appearances have dramatically lessened the impact of the xenomorphs, Alien’s lofty position in the pantheon of great horror movies, and Creative Assembly’s reverence for the source material, made playing Alien: Isolation a truly transportative experience. Every encounter with the xenomorph was the first encounter, all over again, leaving me an utter wreck.

This time, though, I was not just a passive observer, watching Ellen Ripley kicking ass. I was Amanda Ripley, in the shit myself, forced to find hiding places and conserve my flamethrower fuel. All my childhood fears were thus exaggerated ten-fold, which goes some way to explaining why I would spend many sessions largely hiding in lockers and under desks rather than making progress.

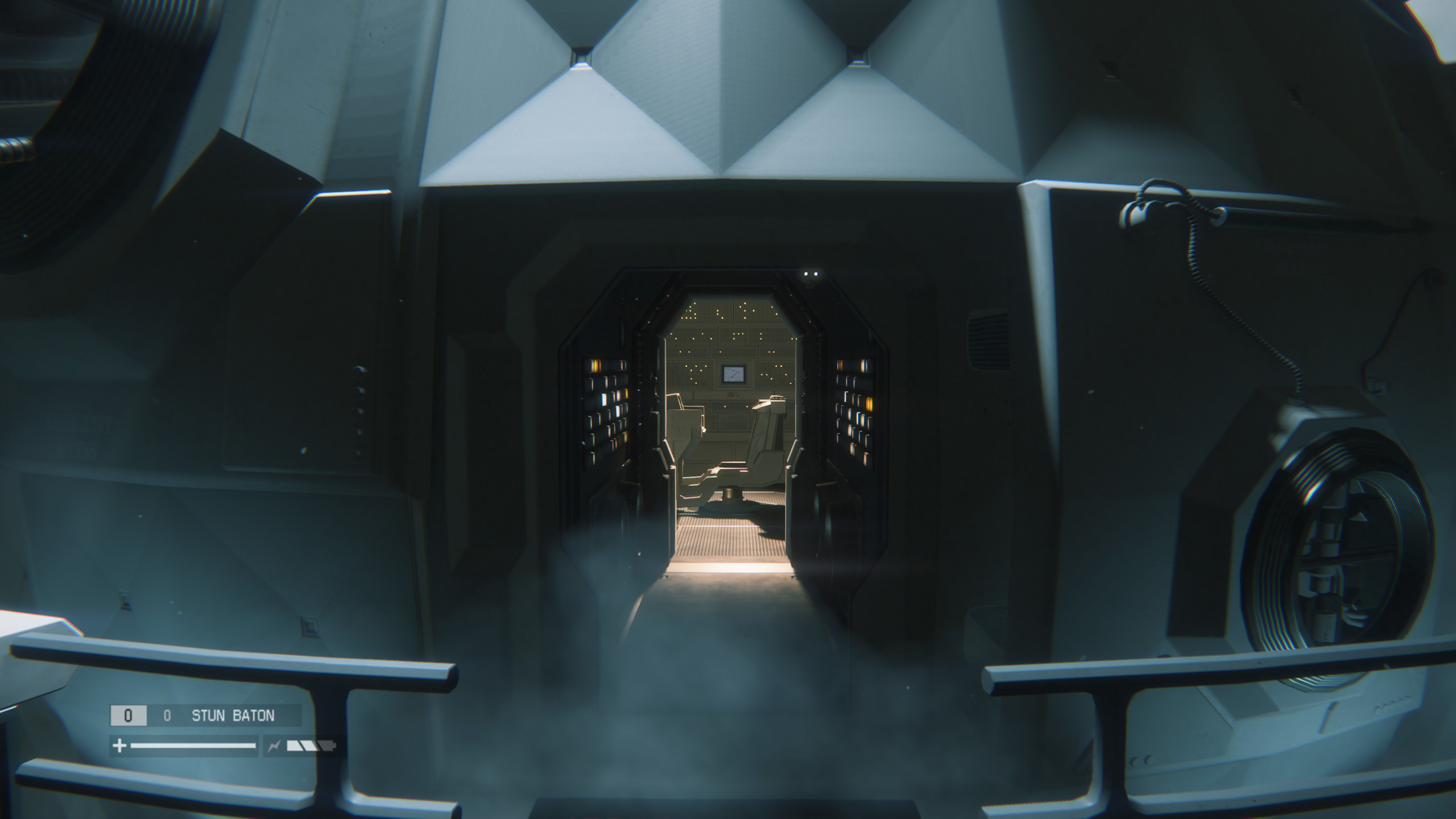

But it’s not just the overt horror elements that Alien: Isolation nails. It’s everything else, too. It’s a celebration of a specific aesthetic: that very deliberate, lived-in, grimy vibe that set the first three movies in particular apart from the sleek, futuristic sci-fi of the previous decade. Some of the decisions, like the analogue nature of Alien’s technology, were products of the era in which it was created, but are now hugely important components—fetishised by a generation which has spent too long smearing their fingers over glossy touchscreens and now pine for the tactile nature of old tech.

It’s the greatest horror game simply because it’s the one that scares me the most.

Alien: Isolation really gets it, and is an extremely tactile experience where much of my time was spent hammering away on clicky-clacky keyboards and wrenching open doors. Every interaction demands physical exertion, something rooting you in place, which not only makes the space itself feel so much more tangible, it makes the horror so much more effective, too, as you mutter “Come on, come on, come on” and hope that the xenomorph isn’t lurking behind you.

More than any other genre, horror games exploit your feelings—your mental and emotional state. There are technically better horror games—Resident Evil 4 is richer and more complex, Amnesia has much better pacing, System Shock 2 is more inventive, The Last of Us is blessed with much more evocative characters—but since Alien: Isolation completely destroys me, drenching me in sweat and causing me to take leave of my senses, it has to sit at the top of the pile. It’s the greatest horror game simply because it’s the one that scares me the most.

Even its flaws are interesting. A quick warning: we are approaching spoiler territory here, so if you’ve taken even longer to get through the game, you might want to bounce now. In some ways, they evoke the journey the series has been on, and the challenge each sequel has to overcome—usually without much success—as it follows perfection. Alien: Isolation’s first half is truly exceptional and terrifying, and there’s an argument it should have ended at around the 10-12 hour mark. You defeat the xenomorph, time to celebrate. But no, there’s more.

As much as the xenomorph is an incredible adversary, I do think it was smart of Creative Assembly to also include human and android threats—they are certainly still in keeping with the source material. I enjoyed the moral quandary that hostile survivors introduced, and I’d usually deploy stealth as my solution in these instances, figuring that they didn’t deserve to die just because they were desperate—though I knew that the xenomorph would probably get them eventually.

The Working Joes, meanwhile, are almost as terrifying as the game’s primary threat. Their glowing eyes, rubbery synthetic skin, polite warnings and measured, consistent pace make them perfect movie monsters, and they are challenging enough adversaries that choosing how to handle them is always a tricky dilemma. One late-game encounter with a room full of them will haunt me forever: a legion slowly marching towards me, all aflame, skin melting, burning arms stretching out to grab me. Horrible stuff.

Neither group is the main course, though, so when the xenomorph initially seems to have been handled, the extended period where you’re dealing with the Working Joe uprising and various human threats sort of feels like you’re being served a starter for dessert.

The revelation that taking out one xenomorph wasn’t enough, and that there’s a whole hive of them now, is a significant departure from the original premise, too. Alien: Isolation is so impressive because, for the most part, you’re being hunted by one alien. The xenomorphs are so dangerous that a single one can take out an entire space station. In the history of the Alien series, adding more aliens has never really increased the horror.

Aliens is one of my favourite sci-fi films, but it’s a gory action movie with lots of horrific moments rather than a straight horror movie. That change works well in a sequel, but in a single game the switch can be a touch jarring. Ripley’s journey through the hive and all those fucking face huggers came close to making me give up on this endeavour entirely. My fear dissipated, but my annoyance increased significantly.

Even though the first half of the game is absolutely the best part, there are still so many great moments—both dynamic and scripted—in the lesser second half. I definitely don’t want to imply that it shits the bed. And, if I’m honest, I was actually glad it overstayed its welcome—even if that did add years onto my playthrough. Just like I’m glad we keep getting Alien movies, despite the fact that every new entry in the series is worse than the last. Well, apart from Romulus, which sits somewhere between Alien 3 and Alien: Resurrection.

Alien was just so good, so groundbreaking, that I can’t blame Ridley Scott and his successors and collaborators for trying again and again and again.

Alien was just so good, so groundbreaking, that I can’t blame Ridley Scott and his successors and collaborators for trying again and again and again. And I can’t blame Creative Assembly for wanting to make something that, at least in terms of horror games, is vast, attempting to capture the feeling of not just Alien but its sequels, while also taking elements from other game genres, like metroidvanias and first-person dungeon crawlers.

While Amanda isn’t a particularly chatty protagonist and displays little in the way of character development—and you could be forgiven for forgetting that she’s Ellen’s daughter or that her ultimate goal is discovering what happened to her mother—her misadventure on the Sevastopol is also one of the series’ few good retcons. In a way, it’s a course correction.

In the theatrical cuts, there’s no mention of Ellen’s daughter, but in the extended cut of Aliens we actually see Ellen and Amanda (who’s not named) having a terse conversation, with Ellen’s decades-long disappearance creating an insurmountable gulf between them. Using motherhood to create stakes and development for female characters is a bit of a reductive, tired cliche, but this series is one where it actually makes sense given the persistence of themes like motherhood and childbirth. In Aliens especially, it elevates the relationship between Ellen and Newt, and makes the latter’s fate in Alien 3 all the more upsetting—the company has once again robbed her of a child.

Alien: Isolation, then, is more than an homage or adaptation, it is meaningfully additive in a way that the tweaks we’ve suffered through since Prometheus have failed to be. It fits comfortably into the series, building on the best films of the bunch without negating or messing around with their pivotal events. We couldn’t ask for better.

There was talk of a sequel, but despite its critical success and the many accolades it’s garnered over the years, the below-expectation sales and high cost of development made it a one-off. But that’s fine. It deserved to be more of a commercial heavy hitter, but I don’t think a sequel is remotely necessary. It did what it set out to do, and then some.

So, happy 10-year anniversary, Alien: Isolation. It’s taken a while, but I am extremely glad I’ve seen it to its conclusion. Maybe I’ll play it again when it hits 20.