For all its ebullience, and for all its palpable enthusiasm for the medium, there’s something deeply weird about UFO 50. The 50-game collection draws its power from constraints: the fictional hardware at its heart, the LX, is an 8-bit system with a 32-colour limit. The resulting aesthetic is immediately recognisable: Everyone knows the Nintendo and Sega systems of this era.

But people are less likely to know about the ZX Spectrum, and I’ll bet few are familiar with the Amstrad CPC 464 mascot Roland. Most people know about the Commodore 64, but can they name five games? (And if so, why isn’t one of them Mad Nurse?) The systems you never got to play are gaps in the continuum. In the internet age, dipping into the catalogue of the MSX platform, or the PC-8800 series of home computers, feels like visiting an alternate vision of the future that just didn’t take.

UFO 50 channels this uncanny atmosphere for me, telling the story of a mysterious 1980s game development studio while keeping to that most fundamental of storytelling tenets: show, don’t tell. Mossmouth isn’t telling the story of UFOsoft: it’s bringing it to life in the form of a whole game catalogue. UFOSoft now exists, and the sensibilities of its four central fictional developers don’t fit neatly with the canon.

We were probably more influenced by the games we didn’t get to play as kids

Eirik Suhrke

I spoke to most of the UFO 50 team—the IRL UFO 50 team—earlier this week. My first point of curiosity was what source they were most inspired by. I told them the UFO 50 collection feels more akin to computer games of the ’80s, rather than the better known console games by the likes of Nintendo, Sega, Capcom et al. The actual point of inspiration was, of course, varied and highly personalised.

“In general, I’ve been very attracted to the aesthetics of computers and consoles that I never owned,” said Derek Yu, Mossmouth founder, Spelunky creator, and one of the six UFO 50 developers.

“We were probably more influenced by the games we didn’t get to play as kids; the stuff we saw in magazines and fantasized about,” said Eirik Suhrke, who not only worked on music for all of the UFO 50 games but also had a hand in design. Tyriq Plummer, who has worked with WayForward and on Cadence of Hyrule, picks up on the thread: “[I like] the idea of being influenced more by the things that you don’t experience, because they live larger in your brain and have more potential. The things you do experience are much more locked in and real in a way that kind of limits them.”

Plummer is the youngest on the UFO 50 team, so he never experienced the 8-bit era first hand: his exposure to those games of yore is via emulation. Yu, for his part, said he feels more indebted to MS-DOS games, while Jon Perry—a tabletop designer who has made games with Yu since childhood—points to early ’90s browser and freeware games as points of reference (Derek and Jon used the now defunct Klik and Play toolset to make games way back then). As for Paul Hubans—creator of The Indie Game Legend and the forthcoming Madhouse—he had the NES firmly in his sights while developing UFO 50.

The game was announced in 2017. Back then, Yu told us that it’d be out the following year. “If we really analysed it upfront and realised it was going to take eight years or whatever, we might not have dived in,” Suhrke said about missing that optimistic deadline.

Members of the team—which also included Downwell creator Ojiro Fumoto, who wasn’t in our call—tended to take directorship over any given game, though most titles involved an element of collaboration and are touched by several hands. During our chat Perry reveals that a game he commandeered—the clever shrinking puzzle-platformer Mini and Max—had a fair bit of input by Hubans. Not everyone on the team knew this, and why would they? No one’s even finished every game.

“We both played all of them a little bit, but yeah… I’ve been watching on Twitch and just seeing new stuff constantly,” Suhrke said. “No one has the full picture.”

Yu continues: “There’s a lot of ‘when did you add that to this game?’ after release. That’s always the best is when you’re surprised by the game that you’re working on. That’s partly why it’s been so enjoyable to work on it for all these years: we’re constantly sharing and surprising each other.”

“It’s interesting to see where we overlap on games,” Hubans said. “With Mini and Max it was very much Jon’s idea, but he let me have a lot of creative liberty with fleshing out a lot of the details at a certain level. And I kind of see that the game where John and I overlap. Then there’s games where Derek and Jon overlap, or Eirik and Derek overlap, and so on and so forth.”

It’s a matter of how far can you push this one idea? How can you maximise whatever this game is trying to be by itself?

Eirik Suhrke

But the influence of each member of the team isn’t as simple as who directed which game, or who might have had a secondary hand in it. “It’s also just the fact that we’ve been hanging out for eight years and playing each other’s games and influencing each other’s designs and, you know, reading each other’s code and influencing each other’s code styles even,” Suhrke said.

“It’s kind of like a band would sort of merge to form one sound: we’ve all influenced each other just by hanging out and playing each other’s games and collaborating in very subtle ways that I’m not sure we could even point out.”

These real world designers aren’t credited according to the individual games they directed or helped make; in the fiction of UFO 50 they’re archivists. The UFOSoft team are fictional characters that aren’t, so said Perry, consistently mapped to any of the flesh world developers.

“But they map a little bit,” he admits, “and that’s just because we all have our own recognizable styles and tics that appear. So it’s not like we would roleplay the same character and make multiple games that would then get assigned to one fictional character. We wanted to produce games that had certain natural leanings and tendencies and then it just became natural to roughly assign those to fictional characters in a way that leverages the sort of trends you could already see in the games, so that the fiction would be more believable.”

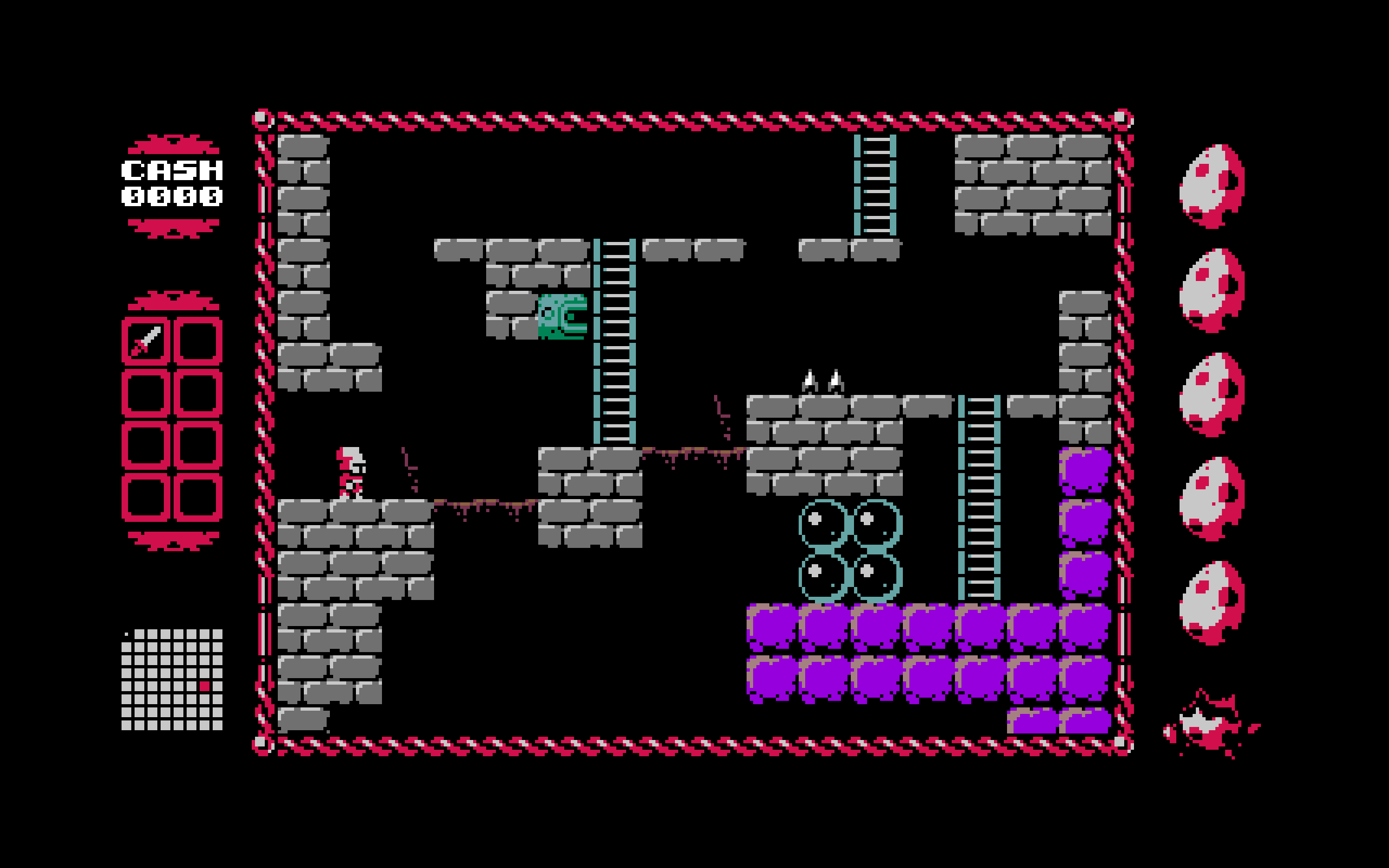

The fiction was there from the start, but the way it unfolds—the evolution of the UFOSoft catalogue—was constantly reiterated throughout development in interesting ways. Take Barbuta for instance, which was (perhaps unsurprisingly) inspired by La-Mulana and Montezuma’s Revenge. It’s the first game in the collection if you’re following the default chronological order, and it’s also one of the hardest and most opaque: if you’re determined to play the games in order it’s an unforgiving introduction. Developed by UFOSoft’s Thorston Petter (in the real world, Suhrke), that game was actually tweaked to be more primitive and less approachable than its original design when the team decided it should be UFOSoft’s “first”.

“That game was not designed to be the first game in UFO 50 chronologically,” Yu said. “I feel like that’s important to note. We weren’t like, ‘we need a first game and it’s got to be a certain way’.

Suhrke continues: “But once it had that position there were certain ways in which we leaned into it. Originally there was normal feedback when you hit an enemy: it would flash and there would be a sound, but then we recognized that if you remove even that [feedback] it feels even colder and more alien to you. And so like every other UFO 50 game it’s a matter of how far can you push this one idea? How can you maximise whatever this game is trying to be by itself? For Barbuta, that was just to make it as unwelcoming as you can; to try to get players to defeat it out of spite.”

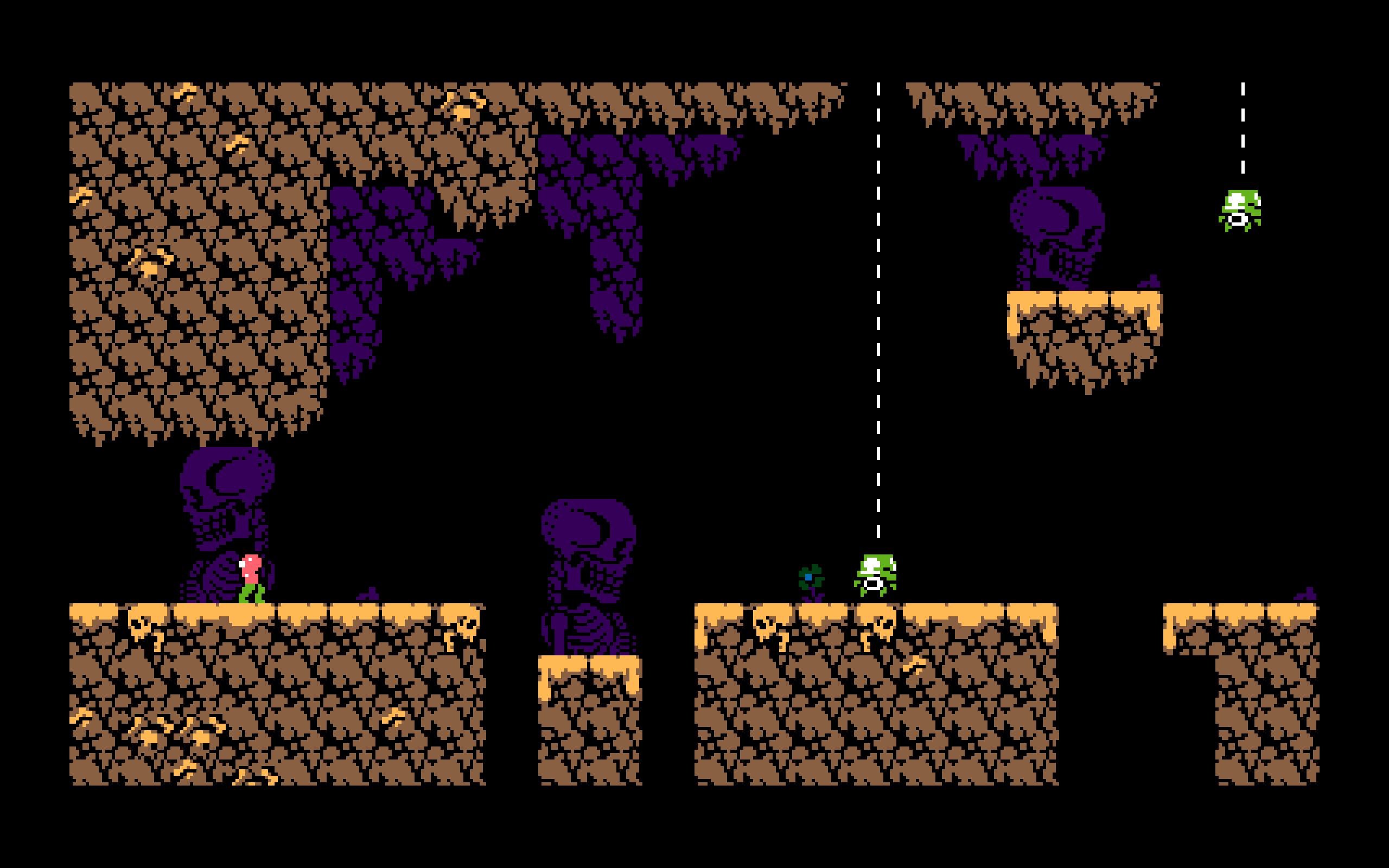

Barbuta’s spiritual successor is another Petter joint, in the form of Mooncat. It’s a platformer with a bizarre two-button approach to movement, which recalls when games didn’t have tried-and-true rules about mechanics as fundamental as movement. It was born of Suhre wanting to make a platformer for a Ludum Dare game jam with a two-button restriction (he said it took a hallucination to come up with the game concept) but it’s a perfect fit for the UFO 50 ethos.

At a time when the industry seems thoroughly down at heel, UFO 50 feels like a rarity: something a handful of people made because they wanted it to exist. Chatting to the team feels like talking to a close-knit group of friends, and none waste an opportunity to mention how much fun it has been to work on the project. “It feels like everyday I’ve been learning from these other people who are just so good at what they do and invested in making something really cool, and finding a way to connect everything has been extremely gratifying as a game designer,” Yu said. “It feels like you’re learning from the work and the other people all the time, every day.”

The team politely declined to discuss the uber-secretive 51st game, which appears to be a meta-narrative about the meta-narrative. Nor would they confirm that a 16-bit UFO collection could emerge. I get the sense that they’ll definitely be working together in the future, though.

“This has been bootcamp for me,” Suhrke said. “I think I’ve become very good at making UFOSoft games. Give me a tube for nutrition and I can keep cranking these out. Assuming I personally keep making games, you’re going to see stuff [from me] that feels like it has the DNA of UFOSoft in it; It’s sort of like a chicken and egg.”