I liked the first two Little Nightmares games, and while I’ve only played an hour of it, I’ll probably like Little Nightmares 3 too. It’s functionally the same. These games are cinematic platformers mixing the solemnity of Inside and Limbo with a surreal, almost Burton-esque take on horror. They’re not mechanically innovative at all; the strength of the series lies in its atmosphere and spectacle, and based on what I’ve played of Little Nightmares 3, that’s not about to change.

And yet, some fairly radical changes have occurred. Tarsier Studios isn’t developing this third instalment, with that job going unexpectedly to Supermassive Games. While Supermassive certainly trades in cinematic horror, most would agree there’s not much Until Dawn and Little Nightmares share in common. Perhaps wisely, Supermassive doesn’t seem interested in rocking the boat, except for one significant addition to Little Nightmares 3: two-player co-op.

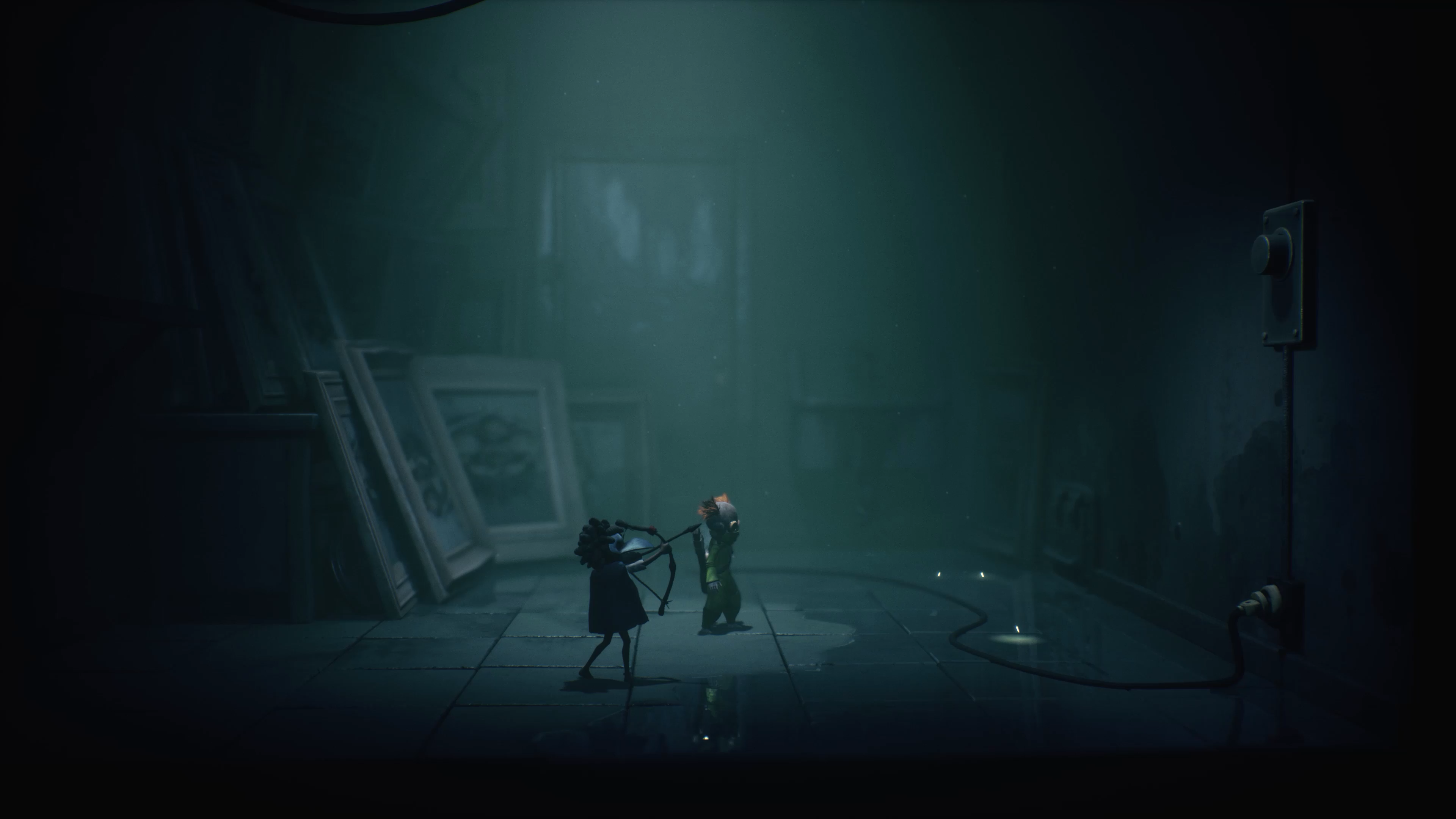

Whether you’re playing alone or cooperatively, Little Nightmares 3 has two protagonists: beak-faced Alone bears a wrench and clown-masked Low a bow-and-arrow. Each tool can be used in different puzzle-solving ways, though to call the obstacles I encountered in Little Nightmares 3 “puzzles” is probably overdoing it. There was a bit of box dragging and a bit of switch hitting with Alone’s wrench. In one room Low needed to trigger a switch with their bow-and-arrow to de-electrify the floor, and in another, someone had to carry a light source to clear a path through hordes of cockroaches. Of course, there was lots of hoisting our co-op partner up to higher levels too.

It’s pretty simple stuff. For solo players, a button press triggers any relevant action from your AI companion; rather than swap between characters like you would in say, Unravel or Trine, your fellow traveller takes matters into their own hands.

Also back are pattern recognition stealth sections. These are rarely complicated, though may involve a bit of trial and error if being still and watching isn’t your thing. During my co-op hands-on we had to evade the notice of a creepy eight-armed old woman who, as far as I could tell, operated the ginormous candy factory we’d been navigating. This required the usual furtive shuffling from cover to cover, though as always, the stakes were raised by the creepiness of the villain. It’s not about the horror of being caught; it’s about the horror of having to look directly at the threat.

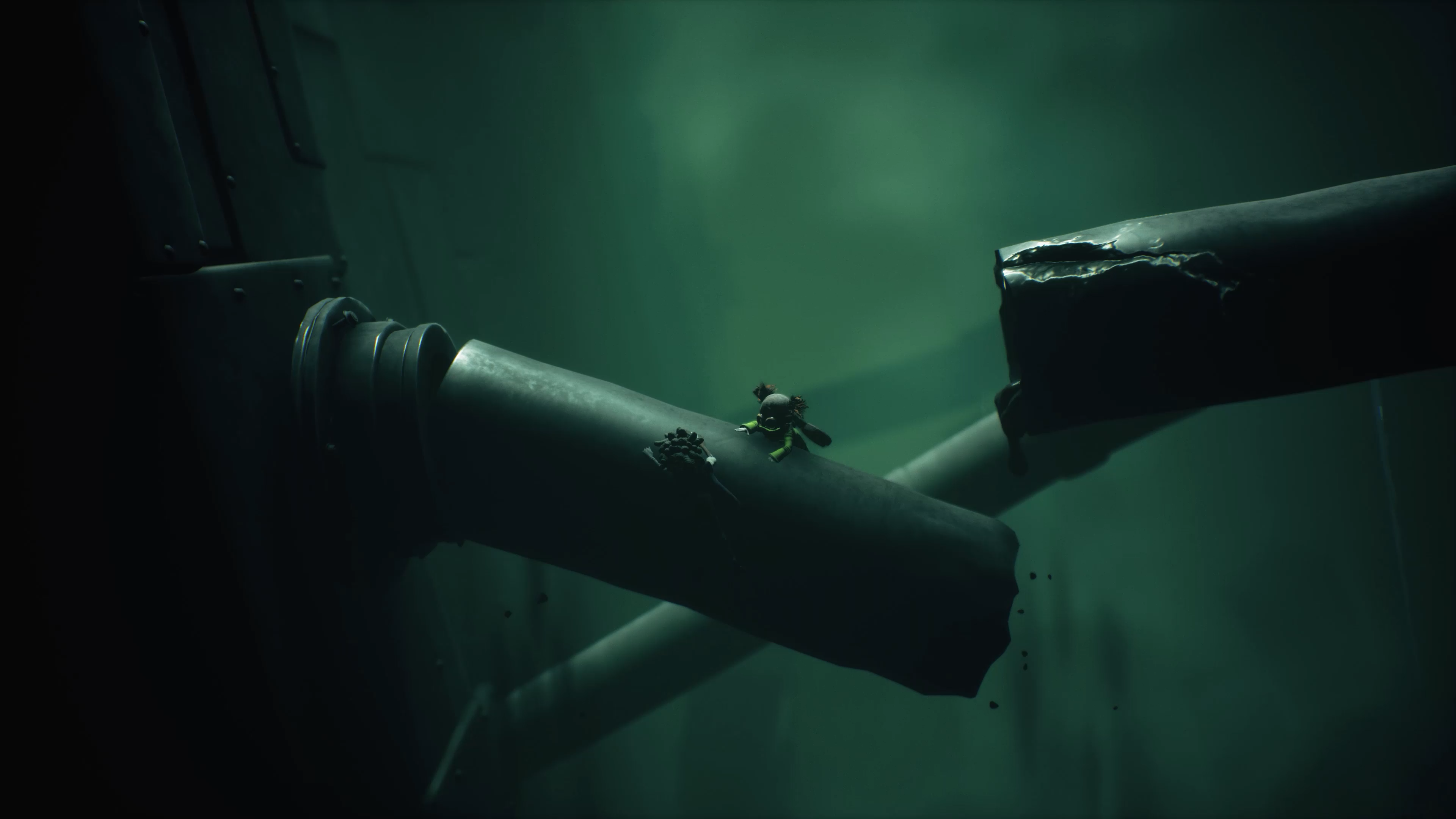

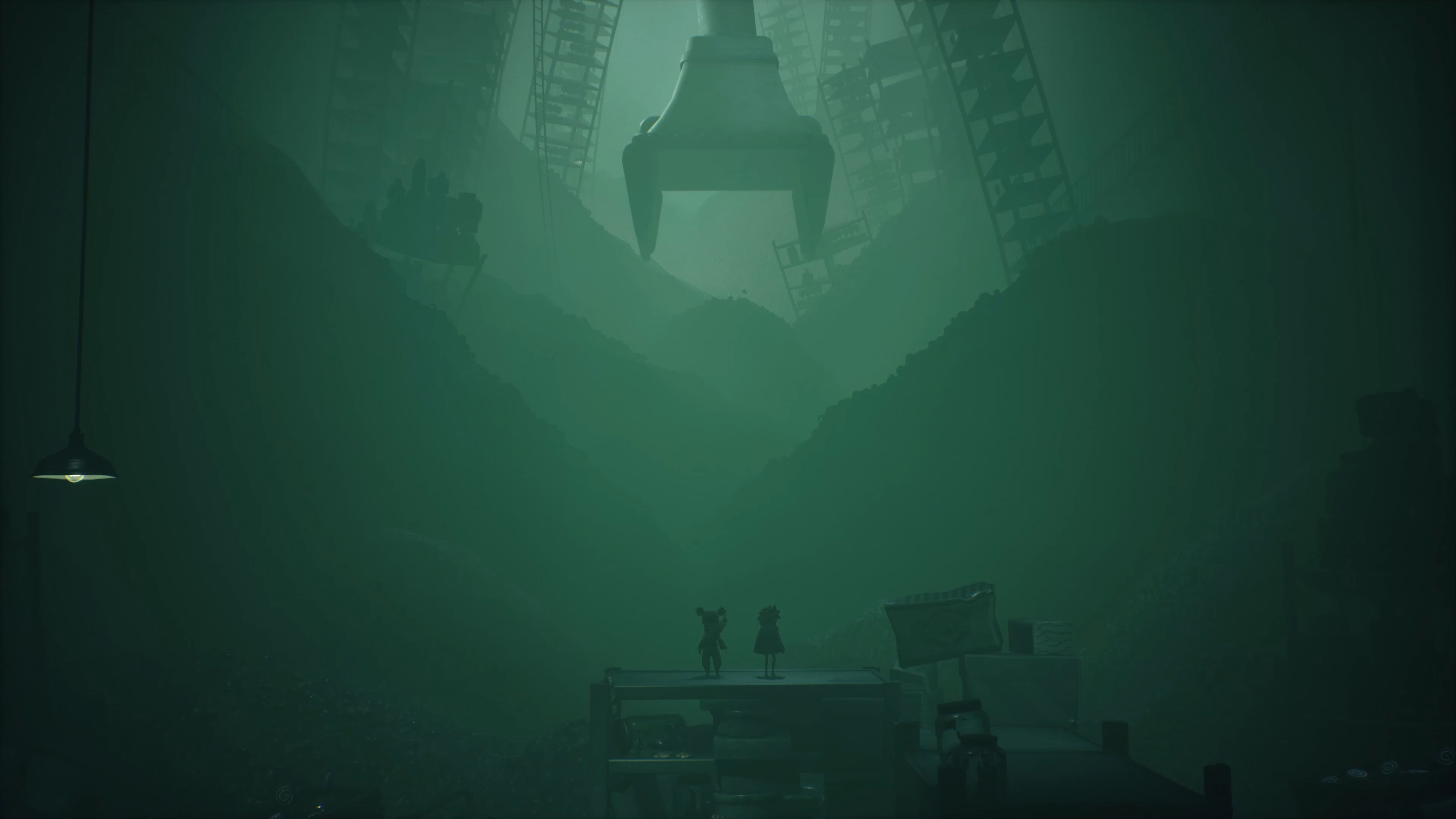

This candy factory by the way is an evil candy factory. The scale as always is immense: Little Nightmares knows how to make the player feel like a dignified weakling in an unbearably hostile world. I pass through a colossal production line where humanoid figures are suspended from ropes and tasked with handling switches. The landscape is cruel and grotesque, but also melancholy and weirdly meditative. The gentle variance of greyscale colour and the pace of the ever-shifting camera has a near-hypnotic effect, and a lack of context or exposition lends the whole thing a dream-like instability, hitting horror notes few videogames are very good at.

There is a grim matter-of-factness to Little Nightmares’ horror: as small figures we move through its world with no hope of influencing anything that goes on around us. We’re not meant to be here and the idea is just to get the hell out. There’s no lack of horror games that steal away our agency and means of self-defence, but few do it with the morbid flair that Little Nightmares does. The threat isn’t always being caught so much as whatever unsettling image might lurk on the next screen.

Later, after wading through waist-high hard boiled candy, I climb a rickety shelf to behold a panorama of Skyrim scale mountains made of lollipop discards. By contrast, I also played a level set in a Necropolis, which I need to cross a sandswept desert to get to. While its dank interiors were less interesting compared to the evil candy factory, it does show that Supermassive Games isn’t interesting in returning to the trauma-evoking domestic horror worlds of the first two games.

I’m really looking forward to Little Nightmares 3 but I am disappointed that the cooperative play is online only: like the aforementioned Unravel and Twine, these kinds of cinematic puzzle games are great fun to play in person. And while I don’t really play this series to have my brain teased, I do hope the final game offers up some more complex problem solving challenges. Those reservations aside, I’m keen to feel like a useless little gnat in an unfathomably corrupted hellscape when Little Nightmares 3 releases some time in 2025.